By Risa Sarachan

The multi-billion-dollar industry of illegal wildlife trade in Africa has long sparked international outrage and warranted media coverage, as many endangered animals are being slaughtered to the point the extinction. A demand for rhino horns in Asia led by international crime syndicates is preying on desperate people living in areas that these endangered wildlife call home. The syndicates incentivize poaching by offering poachers a fraction of the profits.

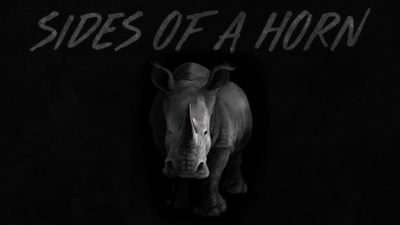

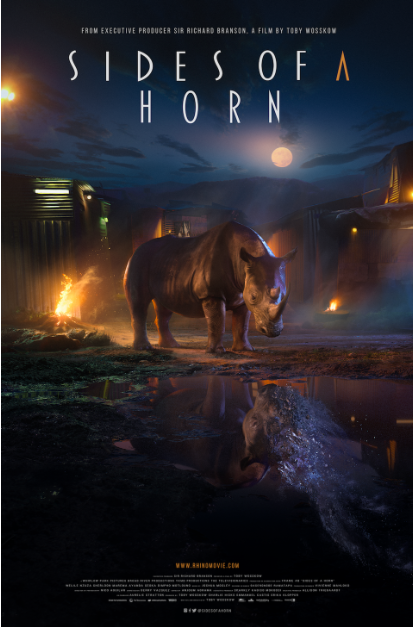

When British-born, Los Angeles-based filmmaker Toby Wosskow traveled on what was initially just a vacation to South Africa, he witnessed the severity of the poaching crisis first hand and knew he wanted to use his talents to take action on this urgent matter. His first instinct told him that he should attempt to contact a man whose long history of global humanitarian work had inspired him since his teenage years, Sir Richard Branson. Branson was eager to get involved and signed on as Executive Producer.

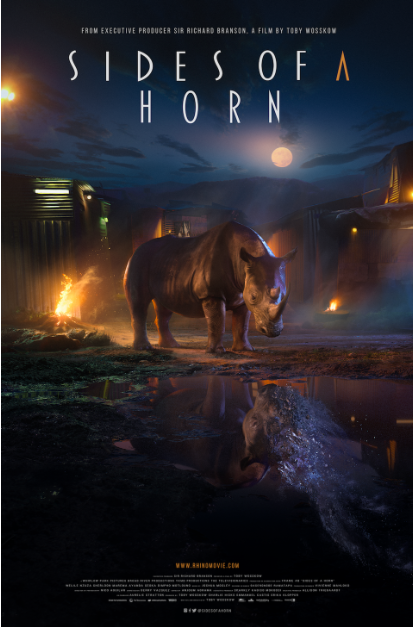

Sides of a Horn is unique in its depiction of the poaching war in that it is sympathetic towards both sides of the struggle in communities torn apart by the conflict between poachers and rangers. Wosskow worked closely with one such community where wildlife crime was most prevalent. Sides of a Horn is a dramatic short film that follows the based on real-life events. It follows two brothers-in-law on opposing sides of the argument, one a poacher and the other a game ranger.

I spoke to Sir Richard Branson and Toby Wosskow about the importance of this film.

Risa Sarachan: Toby, what inspired you to create Sides of a Horn, and how is it a departure from your previous work?

Toby Wosskow: I was actually traveling in South Africa just on vacation exploring, and I was blown away by the natural beauty of the wildlands and the wildlife which was out there in this land that time forgot. I was with an anti-poaching ranger, and we got really close to a rhino. Once we got back to safety, he talked to us for a couple hours about everything that was happening with the poaching war and how close the rhino was to extinction. From that point on, my vacation turned into a research trip. I come from a documentary background so instinctually I started digging deeper and deeper. We went into a few different communities on the border of these protected areas. I learned first hand what you see in the film, which is how people from the same communities are fighting on opposite sides of this same war. They are not just killing wildlife but also tearing apart families and communities. Then when I got back to the United States I started researching a bit further and I found a lot of coverage about the multi-billion dollar illegal wildlife trade, but nobody was really talking about these people on the ground at the heart of the issue, that I had just seen first hand. So I never looked back, I immediately knew that I was going to make this film.

The way we approached the film, we didn’t just go over to Africa and tell the stories about these people, we discussed the stories with them. I literally had to have a meeting with the local royal family. There are a lot of different royal families in the region, they are almost like governing tribes. We met with the royal family and asked the Queen Mother for her permission. From then on, we were partnered with them, showing them every draft of the script. They were collaborating with us, and the community was actually helping us with the filmmaking process. I think that shows. It’s the only way to make a film authentically like this. I’m just really proud that we did it that way instead of just trying to go over and exploit or tell someone’s story that is not our own without collaborating with them.

I started working in documentaries. Since then, I’ve been doing a lot of commercials for Nike, Oakley, and BMW. That’s been for the last two years of my life. I’m extremely excited to be getting back to my narrative roots. I hope that this will continue my career in that direction.

Sarachan: Richard, what compelled you to produce this film?

Sir Richard Branson: One of my favorite places in the world is Ulusaba, Virgin Limited Edition’s game reserve near South Africa’s Kruger National Park, where you can see rhinos and many other great African species in the wild. But poaching has been an enormous problem in South Africa and elsewhere, and I wanted to do all I can to help protect rhinos for the next generation. Rhinos have hardly changed in 50 million years. They are a living, breathing time machine. It will be a tragedy if my grandchildren grow up in a world without rhinos.

Sarachan: How has the film been received?

Wosskow: It’s been really well received so far. We’ve been traveling all over the world with it. Putting it in front of all different types of people, from policymakers to filmmakers at film festivals, to people in Africa who are at the heart of the issue. The first screening was in Los Angeles and one in Johannesburg, South Africa, in September 2018. So, it’s been almost a year that we’ve been screening it around.

Sarachan: I found it unique to see this story presented as fiction as opposed to a documentary. Why did you make that choice?

Wosskow: So, as you said, there have been so many incredible documentaries about environmental issues and poaching specifically, but no one has really done a narrative film. So the decision was definitely based largely on my hopes of introducing the issue to a larger and wider audience. I also think that by telling the story through a human lens by following the characters on this journey, as opposed to an intellectual one, where documentaries usually go, it becomes more relatable and accessible to a broader audience of people who aren’t necessary conservationists or open to these types of issues.

Branson: Sides of a Horn is a fictional narrative, but it’s based on real-life experiences. The film tells a realistic story of the difficult choices people across many of South Africa’s rural communities face every day. You cannot talk about poaching without talking about poverty, inequality, or corruption. The suffering of the animals is closely linked to the suffering of people, and Toby really brings that across. He hopes the film will expose the social impact of the rhino horn trade in a similar way that Blood Diamond exposed the diamond trade, humanizing those on the ground, creating awareness, and catalyzing positive change.

Sarachan: How did Richard get involved as a producer?

Wosskow: I read one of his books when I was about 18-years-old. He has inspired me ever since to find ways to merge passion with purpose. Filmmaking has always been my passion, and I’ve never done anything like this that was social issue based. When I went down this journey and I was looking for partners, of course, I knew about Richard’s work and advocacy with environmental issues. My immediate first thought was, how can I get this in front of Richard? When we eventually did, we heard back almost the next day from him and his team saying, we want to do whatever we can to get behind this. Ever since that day, they’ve been incredibly supportive. They’re the reason that people are going to see this film and I’m just so appreciative.

Branson: I’ve known Toby for some years. We spent time together at the Necker Cup and got to chatting about wildlife conservation and why so much more needs to be done to protect Africa’s great wildlife, particularly the magnificent rhinos. He told me about his film project and asked if I would like to get involved.

Sarachan: Other filmmakers and news outlets have addressed poaching. What makes this topic urgent right now?

Wosskow: Well, first of all, no other filmmakers have given a voice to the people at the heart of the issue. The people in the communities, near these protected areas. That’s why I wanted to make a film. In just the past decade about 8,000 rhinos in South Africa have been poached. I believe the total rhino population is about 20,000. If you’ve lost 8,000 out of 20,000 in the last ten years, that’s clearly not sustainable. Within a decade, there could be no such thing as a wild rhino. We do need to act right now to make sure that doesn’t happen. But also, from a human side, this tension is escalating between rangers and poachers. It’s not just rhino and other animal lives at stake, it’s also human lives.

Sarachan: What can ordinary people do to help after they see your film?

Wosskow: So with the film, we’ve partnered with three organizations, including Virgin Unite. One is the African Wildlife Foundation, who are doing incredible work for exactly what our film is, which is the intersection of wildlife and humans. The other one is WildAid which is more focused on the demand side. Sir Richard Branson is one of their ambassadors. They bring content to certain parts of Asia, where the demand for illegal wildlife products is highest.

Those are incredible foundations that people can and should support. At the end of the film, you’ll see it says to take action at www.rhinomovie.com. When you go there, you fill out a sort of “take action” campaign, where you can use your voice and write to policymakers and campaigns asking them for sanctions, to create more wildlife friendly policies and also to prosecute wildlife traffickers. People can also donate to various organizations, I think it’s important to give people options. You can join the conversation at rhinomovie.com.

Sarachan: How do you re-incentivize poachers to abandon the practice for other types of work? Are there alternative types of work?

Branson: We know that elephants, rhinos and surely lions too, if left alive, have a lifetime economic value that can go into the millions. Live animals, particularly the Big Five, attract a steady stream of tourists seeking to experience these amazing species up close and personal. Their money, spent on accommodation, food and safaris, creates countless skilled jobs, which provide consistent income and opportunity to local communities. We’ve experienced this firsthand at our Virgin Limited Edition game reserves, Ulusaba in South Africa and Mahali Mzuri in Kenya. Sustainable safari tourism is an economically viable approach to conservation that can create alternative economic opportunities for local populations.

Sarachan: What’s fueling this industry? Economics?

Branson: There are many factors at play and the issue needs to be tackled along the entire value chain. In parts of Asia, people pay a higher price for a pound of rhino horn than they would pay for a pound of gold or cocaine. Their irrational demand for a substance no different from human fingernails is fuelling an ideological battle on the ground in South Africa. Many South Africans living near the country’s declining rhino populations face the heart-breaking decision of living in crippling poverty or aiding and abetting the global trade in rhino horn and other illegal wildlife products.

Sarachan: What should the governments be doing? What laws are in place now, and what laws or punitive measures still need to be enacted? Should the UN or other international governing bodies intervene or be allowed to prosecute sovereign nations? Should governments that can’t protect their own wildlife be penalized? How better can we enforce laws in place?

Branson: The worldwide trade in illegal wildlife products is a form of transnational crime that requires global collaboration and alignment – of policymakers, law enforcement, multilateral agencies. Thankfully, much is already happening. Through advocacy and campaigning, we can help drive awareness and reduce demand, but those efforts will only go so far. We must also tackle corruption, weak enforcement of existing laws and lack of conservation and protection resources on the ground to really end this poaching crisis.

Contrary to what Western media often likes to report, Africans care very much about their wildlife and hope that more will be done to end the killing. WildAid, one of our wonderful partner organizations, has conducted a survey in South Africa to gauge public sentiment about poaching. The results speak for themselves: 85 % of all respondents agree that “poaching steals from us all.” The 93% said that rhino poaching, which has reached truly dramatic proportions in South Africa, is a problem for everybody, not just rich, white people. Notably, 96% of respondents think that seeing wildlife is all, or part, of the reason that tourists visit South Africa, but 72% feel that the government isn’t doing enough to end poaching.

Sarachan: How has Virgin Unite helped in the past to fight the poaching epidemic? What are your next steps?

Branson: We have spent much time over the years trying to understand the complexity of the poaching crisis and its global impacts. Working with WildAid and others, I’ve spoken up in Asia to reduce the unacceptable demand for illegal wildlife products, from rhino horn to ivory and shark fins. But you need to tackle wildlife crime from all ends, and so we’ve also supported a number of African conservation projects that seek to protect vulnerable animal populations. Films like Sides of a Horn will help us shed a brighter light on the communities that are most involved in and at the same time affected by the poaching crisis, and I hope it will send a strong message about tackling its root causes on the supply side.

Sarachan: Toby, can I ask what are you working on next?

Wosskow: I won’t say too much, but I’m developing my first feature film with Cathy Schulman, who’s an Oscar-winning producer and she’s been my mentor for the past six years. So I’m currently writing and directing my first feature which she’s producing.

Sides of a Horn will be released internationally in 11 languages on June 25th. Information on where to see Sides of a Horn can found here.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Stay in touch and get the latest WildAid updates.

SIGN UP