By: Brook Larmer

The cryptic declaration from Beijing alarmed and mystified wildlife conservationists around the world. Reversing a 25-year-old ban on the trade of tiger bones and rhinoceros horns, the Chinese government announced in October that it would foster a “controlled” legal market in these goods. The move was unexpected, given that less than a year ago China took a major step in the fight against wildlife trafficking by doing precisely the opposite: banning the domestic sale of elephant ivory. Exotic-animal parts have become status symbols in parts of newly affluent China, but the demand for rhino horns and tiger bones is also driven by an ancient belief in their power to cure everything from fever to impotence.

As if to soften potential criticism, the State Council noted that the horns and bones would come not from wild rhinos and tigers but from existing stockpiles or animals bred in captivity. The reaction was still swift and harsh. Wildlife advocates pointed out that even a highly regulated trade in endangered-animal products can provide cover for continued trafficking; it can also unleash fresh demand that is satisfied by only the killing of more endangered animals in the wild. “This new policy would open the floodgates to the illegal trade,” says Leigh Henry, wildlife policy director at the World Wildlife Fund in Washington. “Wild rhino and tiger populations are at such low levels that there is no wiggle room. If it goes wrong, that’s it. The species are not coming back.”

In November, unexpectedly, China seemed to back down. A government usually impervious to criticism postponed its plan in the face of the growing uproar from environmental groups, the United Nations and signatories to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. For now, the government is keeping in place its “three strict bans”: on the import and export of rhinos, tigers and their byproducts; on their sale; and on the medical use of rhino horns and tiger bones. The State Council order has not been rescinded, however, and wildlife conservationists know that the potent economic forces driving the wildlife trade are not going away anytime soon.

Behind China’s Hamlet moment — to ban or not to ban — lies a deeper question: Why would Beijing push a policy that undermines President Xi Jinping’s oft-stated ambition to build an “ecological civilization”? Over the past few years, China has tried to refashion itself as a responsible global leader on climate change and environmental issues. It has also become a champion of wildlife conservation. China’s total ban on the sale of ivory, a widely applauded move designed to help protect elephants, took effect at the end of 2017. This decade, Chinese consumption of shark fins has dropped by 80 percent. A campaign by the wildlife-advocacy group WildAid ran on Chinese digital media, keying in on the fact that rhino horns provide no more health benefits than other sources of keratin by showing a string of Chinese celebrities — all biting their fingernails. All this progress, though, can’t offset China’s central role in stoking the illegal wildlife trade.

With estimated total revenues of up to $23 billion a year, wildlife trafficking is now considered the world’s fourth-most-profitable criminal trade after drugs, weapons and human trafficking. Even with China’s ivory ban, at least 20,000 elephants are poached each year for their tusks — 55 dead elephants a day. More than 7,000 African rhinos have been slaughtered for their horns in the past decade. The rate of poaching for tigers and rhinos has slowed, and the price of rhino horn — not long ago almost twice as expensive as gold — has dropped by two-thirds, according to WildAid. But the gains are fragile, the dangers ever-present. In Namibia, investigators told me that criminal networks are plundering animals, like colonies of brilliantly hued carmine bee eaters and families of pangolin, the scaly anteater that is the most trafficked mammal on the planet. Almost all are destined for China.

So, then, why the contradiction? The answer may be found in an odd confluence of two forces in 21st-century China: rising affluence and the resurgence of practices associated with traditional Chinese medicine. Developed more than 2,000 years ago, traditional Chinese medicine centers on the belief in qi, or vital energy, which regulates our bodies through a balance of yin and yang. Ailments, seen as imbalances, are treated with acupuncture, massage and breathing exercises, along with herbal remedies that sometimes use parts from animals like scorpions and sea horses. Traditional medicine’s governing bodies have urged practitioners not to use endangered animals, with limited success. For the Chinese government, the obstacle to ending the wild-animal trade isn’t just the domestic popularity and profitability of traditional medicine. It’s also complicated by the fact that traditional medicine, a $130 billion industry, has become a valuable form of soft power that China is exporting around the world.

Traditional medicine may conjure images of folk healers and spiritual gurus. But over the past few decades, it has been mainstreamed as part of the state medical system, sold as a viable alternative for an aging population. In 2017, it grew by 20 percent, fueled by more than 4,000 traditional-medicine hospitals across the country. Now China is aggressively promoting the practices overseas. In May, Beijing announced that it is developing 57 traditional medicine centers this year in countries that are part of its globe-spanning Belt and Road Initiative, like Poland and the United Arab Emirates. In 2017, China’s exports of traditional Chinese medicine reached $3.6 billion. This year, for the first time, the World Health Organization included details of traditional Chinese medicine in its all-important annual compendium of diseases and health problems.

That a medical system aimed at achieving balance should be held responsible for a calamitous imbalance in the natural world is one paradox of the wildlife trade. Leaders in traditional medicine understand the bad optics. Rhino horns and tiger bones were removed from its official pharmacopoeia 25 years ago, and in 2010, the World Federation of Chinese Medicine Societies, hoping to stem their use, dismissed many of the health benefits of tiger bones. But this did little to stop entrepreneurs from selling tiger-bone and rhino-horn health products. And far more species are at stake. Visitors to the market in the town of Mong La on the China-Myanmar border can reportedly find hundreds of endangered animals on sale for supposed medical purposes: pangolin scales (to stimulate lactation or relieve skin diseases), bear bile (to treat liver or gallbladder conditions), tiger penises (to cure impotence).

If these were normal products, with plentiful supply and steady demand, a well-regulated legal trade might reduce both prices and incentives for poaching. But the economics of the wildlife trade are hardly normal; it behaves more like drug trafficking would if opium and coca plants were in danger of going extinct. Conservationists point to the experience with elephants as a tragic and cautionary tale. In 1999 and 2008, tons of stockpiled elephant ivory were sold in order to ease rampant poaching. There is evidence that the sale had the opposite effect. “It doesn’t work like kitchen-table economics,” says Alexandra Kennaugh, a wildlife conservation and trade expert at the Oak Foundation who has studied the behavioral economics of the rhino-horn trade. “I’m not at all opposed to trade of some species under the right circumstances, but the latent demand in China for rhino horn is much higher than what could be produced by farms or other available supply.”

Over the past decade or so, Chinese businessmen have set up dozens of captive-breeding farms for tigers and rhinos in China and neighboring countries. Debbie Banks, tiger campaign leader at the nonprofit Environmental Investigation Agency, estimates that 5,000 to 6,000 tigers live in dismal conditions in these facilities around China, almost double the number in the wild across Asia. Some are raised solely for skins, bones, teeth, claws and penises that can eventually be funneled into the wildlife trade, Banks says. About a third of the material in the Asian tiger trade now comes from captive tigers, she says, including the bones that go into tiger-bone wine sold outside a couple of the facilities. “The value of a tiger is not simply the sum of its body parts,” Banks says. “It has value alive in the wild — for the ecosystem, tourism, culture, even aesthetics. In China it’s seen simply as a commodity.”

Environmentalists suspect that captive-breeding facilities in China have been pressuring Beijing for years to reverse its ban and open a regulated trade in tiger bones and rhino horns. They seemed to have finally succeeded — at least for two weeks. The owners of these farms would presumably reap a windfall if their “products” could be legally traded in the Chinese market with the government’s imprimatur. Even greater pressure may have come, conservationists say, from the big pharmaceutical companies that produce traditional medications. And then there are the stockpiles. Most are well-regulated, but in an industry defined by scarcity, the value of a stockpile rises as the number of the animals in the wild falls. (In 2012, economists writing in the Oxford Review of Economic Policy even postulated that some stockpilers might be “banking on extinction.”)

What would happen if China changes course again? Making the trade in tiger bones and rhino horns legal, giving it legitimacy, could spark a demand that overwhelms the supply. Extinction would loom. “It would be disaster to go down that road,” Peter Knights, WildAid’s chief executive, says. “There are now tens of thousands of consumers. What if they become millions?”

Stay in touch and get the latest WildAid updates.

SIGN UPAbout WildAid

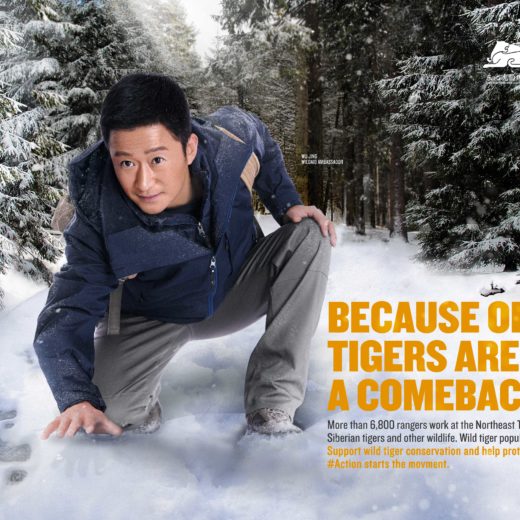

WildAid is a non-profit organization with a mission to protect wildlife from illegal trade and other imminent threats. While most wildlife conservation groups focus on protecting animals from poaching, WildAid primarily works to reduce global consumption of wildlife products such as elephant ivory, rhino horn and shark fin soup. With an unrivaled portfolio of celebrity ambassadors and a global network of media partners, WildAid leverages more than $308 million in annual pro-bono media support with a simple message: When the Buying Stops, the Killing Can Too.

Journalists on deadline may email communications@wildaid.org